Most municipalities in the Legal Amazon do not have land assets

In an interview with Concertação, Dr. Luly Fischer, professor of Law and member of the Postgraduate Program in Law and Development in the Amazon at the Federal University of Pará (UFPA), explains why many cities in the Legal Amazon do not even own their own headquarters.

It demonstrates that having its own land heritage is vital for Brazilian municipalities and analyzes the consequences of the lack of this heritage for numerous aspects of life in (and in) cities in the Legal Amazon. The professor also addresses the impacts of this reality on the viability of public policies and possible solutions. Check it out:

1) Why do most municipalities in the Legal Amazon do not have their own land assets?

In the First Republic (1889-1930), there were other priorities for defining limits by the federated states, as well as the need identification of private areas so that areas not occupied by private individuals (vacant land) could be collected for municipal authorities.

From the 1930s onwards, the process of federalization of land began in the North Region. This process reached its highest level in the 1960s and 70s of the last century, removing from states the ability to allocate land to emancipated municipalities.

Today, most of the municipalities in the region date from the second half of the 20th century, and the federated states have little or no almost none of the property to donate to the created municipalities.

In turn, the land market is also not stable for carrying out expropriations or approving formal subdivisions, which creates dependence on allocations by the Union.

After 2009, the National Institute of Colonization and Agrarian Reform (Incra) relaxed the rules for the acquisition of this heritage by municipalities. Most of the land is suitable for immediate allocation, but the characterization procedure of the Union Heritage Secretariat (SPU) in the region is still low, which impedes the speed of the process.

For municipalities to be able to manage this heritage properly, a policy aimed at overcoming this bottleneck is necessary, as well as a process monitoring.

2) Are there official data on the patrimonial situation of the municipalities in the Legal Amazon? span>

There is no consolidated data on the patrimonial situation of the almost 800 municipalities that make up the Legal Amazon. To arrive at approximate data, the only way is to analyze the reality of each state and the process of municipal emancipation.

For municipalities existing until the 1930s, with the exception of the state of Acre, there was an attempt to allocate vacant land or the recognition of donations made during the colonial/monarchic period, in a process similar to what occurred with the allocation of municipal assets in other regions of Brazil.

However, the allocation process did not occur systematically in areas of former territories (Amapá and Roraima), nor in municipalities created and emancipated since the 1960s, in areas influenced by highways built since then.

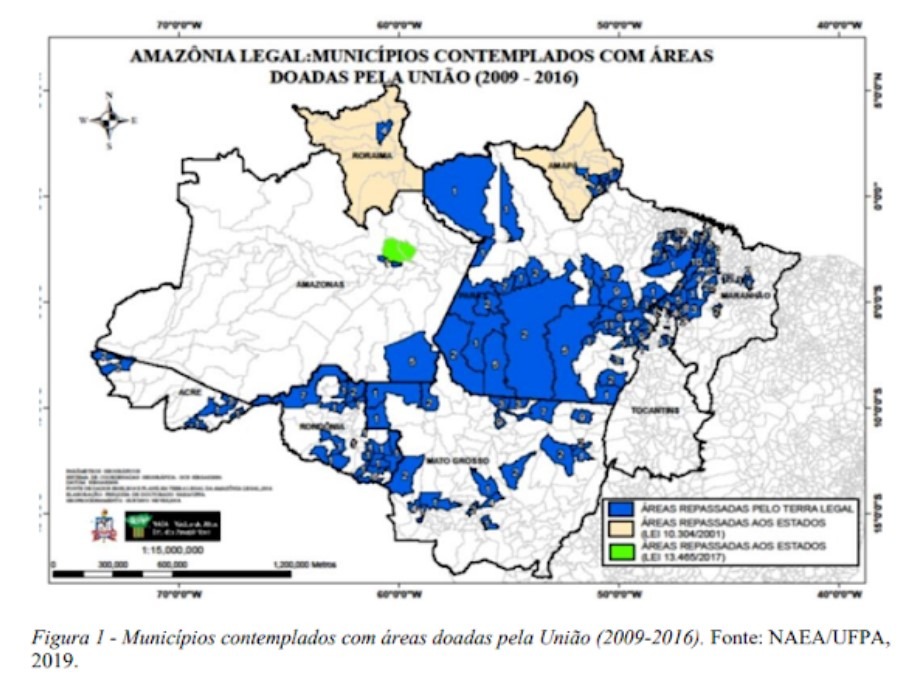

In these cases, there was a significant allocation of areas collected and registered in the name of Incra that lost their productive destination as a result of the urbanization, during the Terra Legal Program (Law 11,952/2009). Quantities are detailed in this spreadsheet, which we used as a basis to create the figure below:

I emphasize that the allocation may continue to occur through Incra, but I am not aware of any allocations completed during the last administration (2019-2022). These allocations need to be requested as donations by the municipalities, and not all of them did so due to lack of knowledge or availability of technicians to instruct the processes.

The areas on the banks of rivers and islands are managed by the SPU. For most states, there is still no characterization of federal assets, which makes it difficult to allocate them like the one that occurred during the Terra Legal Program.

Another difficulty is that it is up to the municipality to pay for the entire SPU survey process, and there is no certainty that the transfer will occur during the same administration. Furthermore, water mirror areas and floodplains have legal limitations on their destination, as do those located on border strips, which makes the operationalization of the process practically unfeasible in many situations.

In 2017, the National Congress began the process of stateizing the heritage of former federal territories, but the procedure is not yet finished. In these cases, in which the allocation process took place in the First Republic or is still pending, urban regularization will occur by the state and no longer by the Union.

3) What are the main consequences of this situation?

The negative consequences are multi-scalar and are not limited to the reality of cities. Among them, the inability to obtain resources from the federal government for the implementation of public equipment and the low effectiveness of plans to control land use and occupation stand out, the regulation of which does not reach public goods.

Other problems arising from the absence of land assets involve low property tax collection, the advancement of the informal land market and the difficulty in promoting housing improvements.

It is also worth highlighting the ease of hiding personal assets, the low incentive to formalize economic activities and comply with standards labor and environmental issues and, finally, the use of violence to resolve conflicts.

4) What would be the ways to correct this situation?

To resolve the situation, several actions must be carried out in a complementary manner. Firstly, it is necessary to encourage urban land regularization in consolidated areas through approval by the Union, without the need for donations or the signing of cooperation terms. The areas would be transferred directly to private occupants, whether individually or collectively.

Furthermore, to maintain the destination through the donation of areas being consolidated by the Union in accordance with locally approved urban planning , it is important to work to overcome the application of the limit of 2500 hectares for municipal entities, provided for in the Constitution.

Regarding national legislation, it is necessary to adapt it to simplify urban planning for small municipalities in the region. Rural, socio-environmental and ethnic dynamics must be considered, as well as seasonal housing and production dynamics for the purposes of recognizing the population’s right to housing.

We cannot forget the importance of creating public policies for the land regularization of water bodies and floodplains that do not imply the mischaracterization of existing socio-environmental processes.

Finally, for all these actions, it is essential that technical assistance and multidisciplinary monitoring programs are created to guide the process of allocation of these areas to municipalities by the Union and federated states;

For greater depth on the topic and knowledge of a case study (Parauapebas, PA), access the thesis doctoral degree from Prof. Luly Fischer, in which the territorial planning model of French Guiana is also presented: https://repositorio.ufpa.br/jspui/handle/2011/7502