Becoming acquainted with Carmézia Emiliano’s work is delving into the artist’s ongoing effort to record every detail of the culture of her people, the Macuxi. Art whose every line, color, shape and scene reflects a choice, and is meticulously constructed in coherence with her “mantra”: “I paint so as not to forget my culture”.

A desire so ingrained in her that it made her astonished when asked why she had never painted Boa Vista, the city where she has lived in for over 30 years. Despite having lived in the capital city of Roraima for quite long, the city does not offer her memories that she wishes to paint. “Maybe one day I’ll paint a picture of indigenous people who abandon their tribes and come out here,” she replied.

Carmézia’s canvases with their scenes from Macuxi everyday life, their myths and rites, festivals, their relationship with nature and ancestral knowledge, painted in bright colors and a plethora of details, catch the eye. Her perspective as an indigenous woman also captures nuances of the division of labor between men and women in activities such as planting, hunting, preparing food, and childcare. The vivid scenes appear in repetitions, like an amulet against oblivion.

“Giving out your first work of art is no good”

The artist was born in Maloca do Japó, a Macuxi village in the Raposa Serra do Sol Indigenous Land (RR), in 1960 and moved to Boa Vista in the late 1980s in search of work. It was there that she met her husband, Léo Malabarista, a circus artist, with whom she began to attend cultural events in Roraima

In 1992, she visited her first art exhibition, which featured works by Eliézer Rufino, brother of the poet Eliakin Rufino1. There, she realized her desire to become a painter as well. It was Eliakin who presented her with a canvas and paints so that she could try them. In a statement to Roseli Anater, Carmézia said that she didn’t think of anything she wanted to paint, but inspired by a painting by Eliézer depicting a buriti palm tree, she decided to paint one as well. She then offered painting “Veado no buritizeiro” to Eliakin, but he refused, saying that “giving out your first work of art is no good…”.

From then on, Carmézia never stopped painting. Initially, as she had trouble buying paints, she produced her own from leaves, fruits, seeds and other elements of nature, as she explained in an interview:

“I produced paint myself using green chili pepper leaves, purple cotton leaves, and annatto, which is called colorau, jenipapo brabo, coal, yellow potatoes, things that come from nature. I used to make these colors, I would crush the leaves and then I would draw on paper, not on canvas, because the canvas barely holds it (this paint). Then I painted on paper using these colors.”

In Carmézia’s work, painting is an affirmation of Macuxi culture

Her themes come from Macuxi life and culture, which she paints so as not to forget, and to share with other people. In her words:

“My story is beautiful, because I was born an observer, I grew up an observer. I was born in nature, I grew up doing things, I grew up in the community, in the forest, working in the countryside… I watched everything my mother did. (…) I depict these memories on canvas: making beiju3, making caxiri4, grating cassava, weaving cotton, making hammocks.”

The characteristics of her work place her as a notable representative of naïf art in Brazil, a movement that uses bright and cheerful tones, simple forms and the idealization of nature, in contrast to more usual artistic techniques, such as perspective, conventional forms of composition and use of colors.

The artist’s trajectory outside of the Roraima circles in the following decades is a reflection of the constant growth in the quality of her work, the appreciation of her style and indigenous art.

Carmézia was a constant presence at the Sesc Piracicaba Naïf Biennial from 2006 to 2020, the year in which she received authentic recognition in the contemporary arts circuit. Since then, her works of art were exposed in major museums, exhibitions and galleries, such as MASP (São Paulo Museum of Art), São Paulo Biennial and Biennial of the Amazons in Belém (PA), as well as abroad. An experience that has given her the opportunity to visit other places, meet other artists and, most importantly, to show her culture.

Carmézia’s work inspires Concertação’s digital channels

As of August 2024, Carmézia brings into the Concertation’s visual identity inspiration from ten paintings: “Fazendo beiju”, “Araras”, “Contando histórias”, “Estudando”, “Fazendo panela”, “Moqueando peixe”, “Maloca do Contão”, “Quatis”, “Wazaká” and “Pescaria”, made available by the Augusto Luitgards Collection. The artist spoke about some of them.

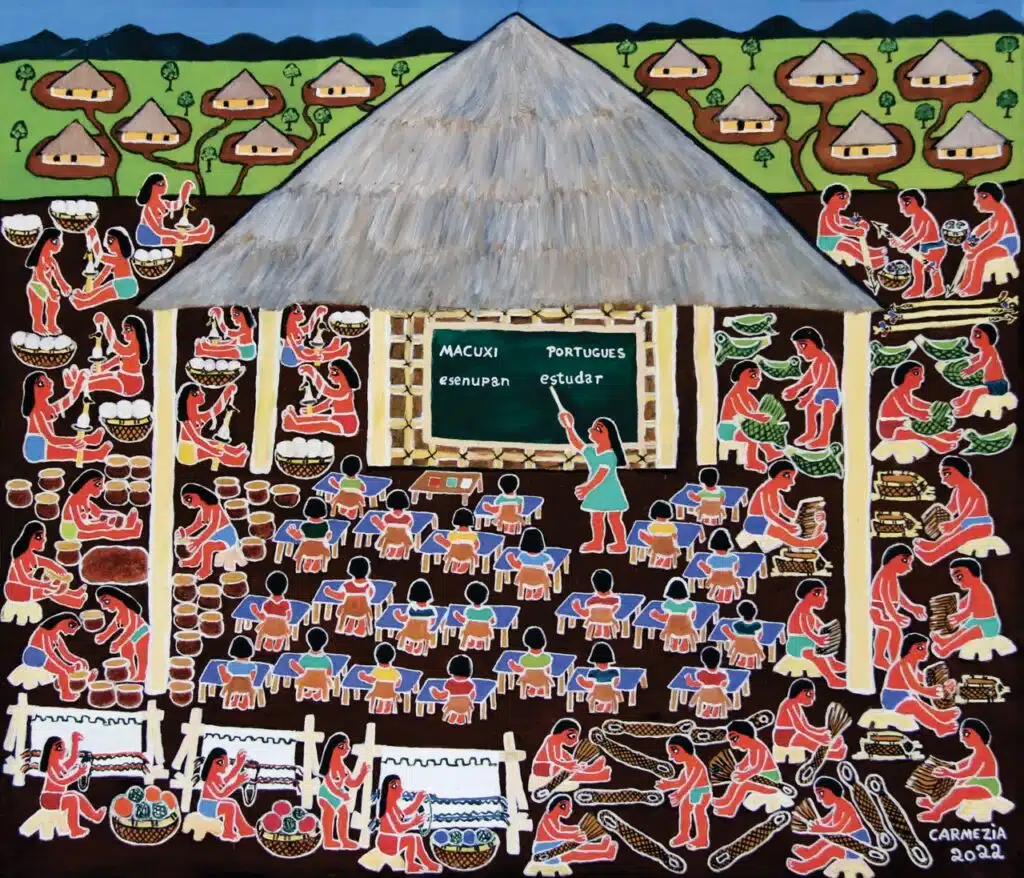

ESTUDANDO (2022)

In this work of art, which portrays a school, one can see a teacher teaching Portuguese and Macuxi. Emiliano says that ever since she was a child, she has never stopped speaking the language of her people, but her daughter cannot speak it, and many young people prefer to speak Portuguese. Therefore, around the school, she portrayed her grandparents teaching traditional knowledge, highlighting its relevance for the continuity of the Macuxi culture. These are activities such as making hammocks, tipiti5, braiding, shredding cotton, making arrows and clay pots.

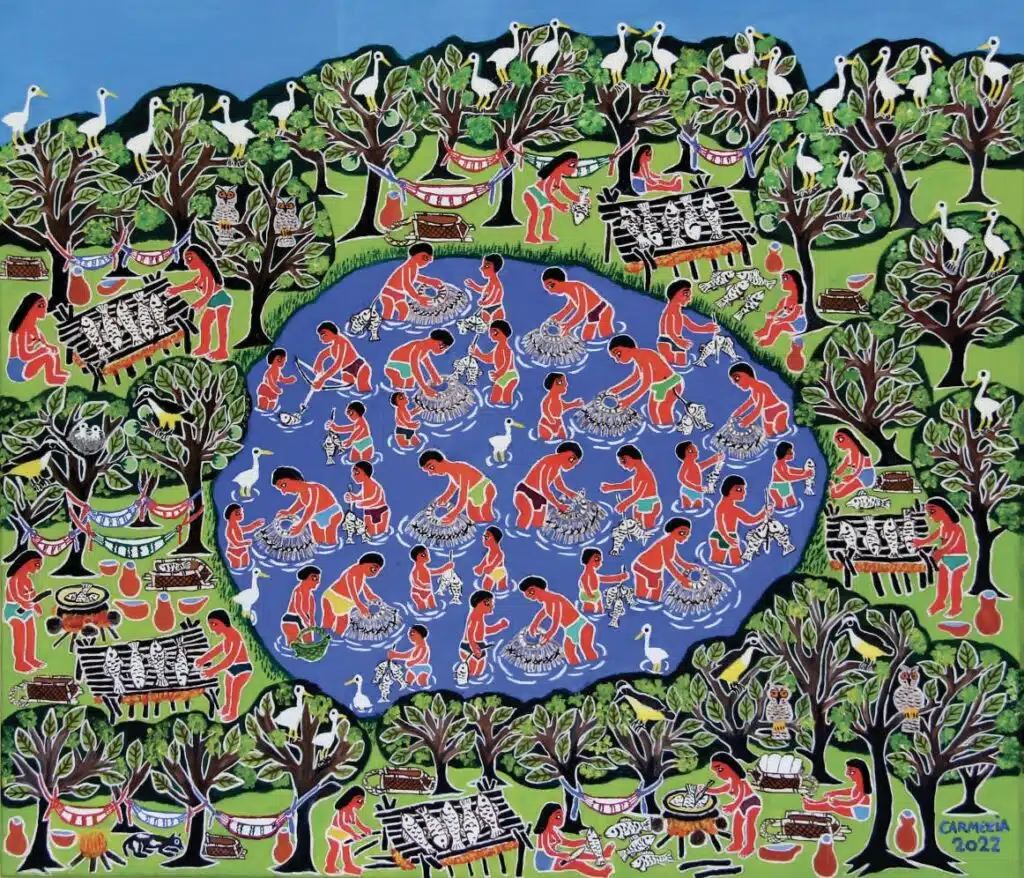

MOQUEANDO PEIXE (2022)

“This canvas shows the way we live. Because we don’t have a shop to buy food, we don’t have money to buy nylon thread, we live off the land and fishing (…). When we go fishing, we take the jiqui6. Here, the men and boys are fishing and the women are “moqueando” (roasting)7 the fish.”

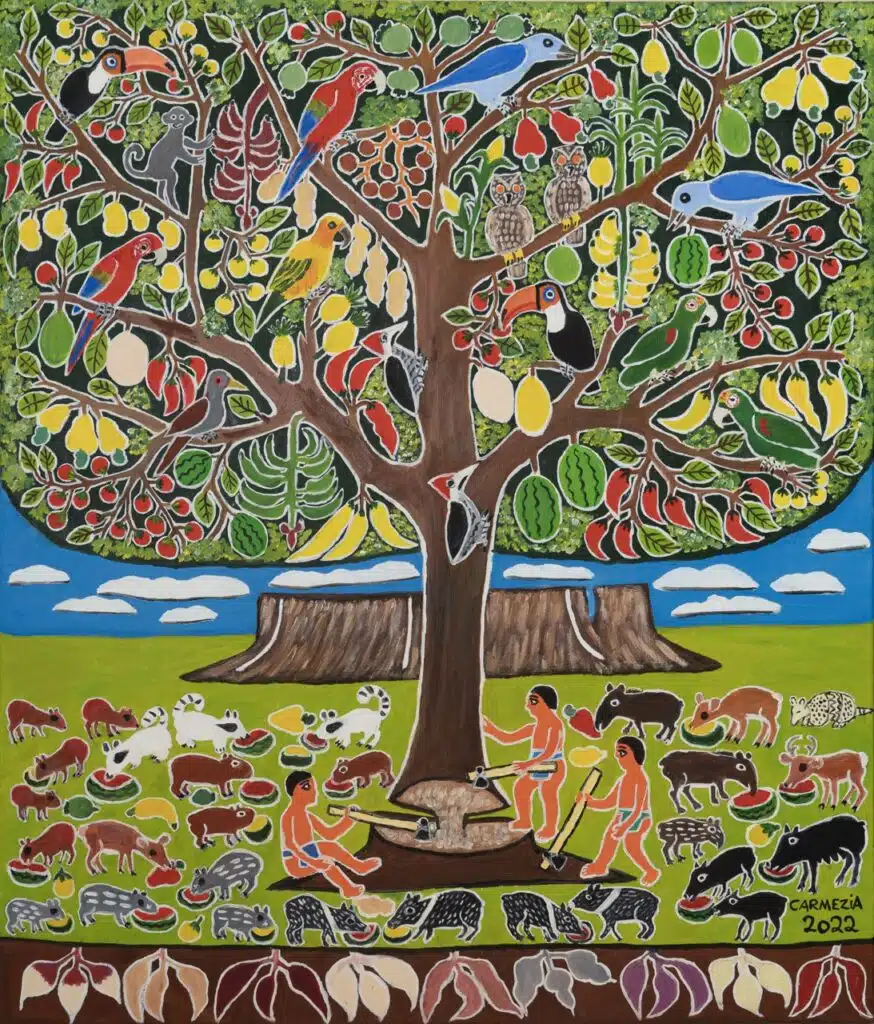

WAZAKÁ (2022)

Founding myth of several indigenous peoples of the Amazon, Wazaká is the name of the Tree of Life and the legend of the emergence of Mount Roraima. According to the story that Carmézia’s uncle told her, brothers Ariqué and Esquirã starved because they didn’t know where to find fruit. They had an agouti, and one day the little animal slept with its mouth open, revealing fruit remains between its teeth.

The next day, Ariqué and Esquirã followed the agouti and found this huge tree. As there was no fruit on the ground, they decided to cut it down to reach the ones that were higher up. The tree fell to the north and this is why there are many fruits in that region. From the sap that flowed down the trunk, the Maô river in Guyana, the Urariquera river in Venezuela and the Branco river in Brazil emerged. So, Ariqué and Esquirã turned the tree trunk into a mountain, which is called Mount Roraima.

“My art takes me places I never thought I would go to”

Carmézia’s wish now is to continue painting and display her work abroad. She has already exhibited in the United States, but he wants to take Macuxi culture even further.

“If it weren’t for my art, I wouldn’t be able to see the world. I didn’t expect to get to these places through my art, but I’m very pleased, because it is very important for me to be able to show my culture to the entire world”.

NOTES

- Eliakin Rufino is a poet from Roraima, writer, philosopher, university professor, cultural producer and journalist. ↩

- Master’s Dissertation UFRR 2014: “Painting so as not to forget: The visual and oral narratives of Carmézia Emiliano” (http://www.bdtd.ufrr.br/tde_busca/arquivo.php?codArquivo=189) ↩

- Beiju:dish of indigenous origin; tapioca ↩

- Caxiri: traditional alcoholic drink of the indigenous peoples of the Amazon, made from cassava ↩

- Tipiti is a type of press or woven straw squeezer, used to squeeze, drain and dry roots, usually cassava.. ↩

- Jiqui: River fishing trap, consisting of a long, tapered basket ↩

- Moquear: roasting or smoking fish on a moquém, a handmade grill supported by wooden forks stuck in the ground ↩