The techniques that she uses are as diverse as her inspiration, including photography, “lambe-lambe”, graffiti and collage. Self-portraits are very present in her work, as a study of her black body’s image occupying the city’s spaces.

They are scenes from everyday Amazonian life that bring facades, fruits, colors, smells, objects and childhood memories, in which chaos follows her frantic thinking and incorporates different topics and languages.

Whether through urban interventions, crafts or exhibitions, the artist triggers overlapped questions that lead viewers to confront their own conception of the world, the Amazon, the city and the other.

Upon hearing repeatedly that she “dreamed too big” and that she would never be able to achieve her dreams, Dacordobarro understood that she needed to see herself as “a very big individual to reach places that are bigger than me”. .

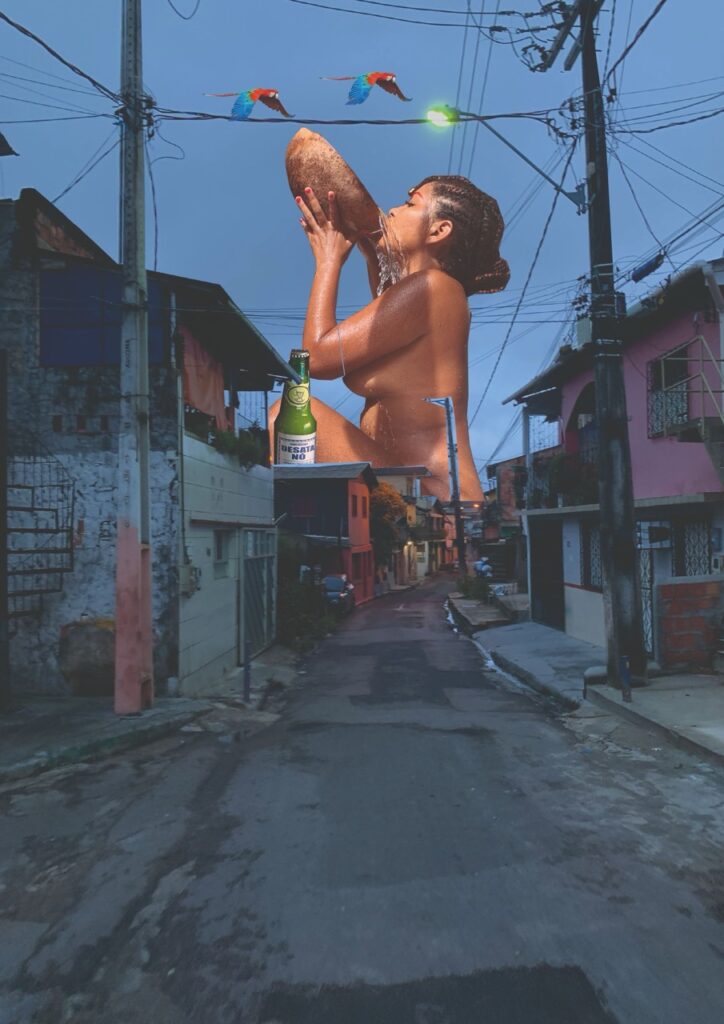

In this work, which is being displayed for the first time, she appears bigger than the city, confronting her neighbors, racism, sexism and the limits imposed upon her. It portrays the street where she lived, in Manaus, and reveals her consciousness that she was able see the world beyond what people told her was allowed. “Dream more, achieve more There is a universe beyond my neighborhood or the borders of Manaus that I can also aspire”. At the top right, her mother’s hand is portrayed handing her a fig, a symbol that, according to Umbanda, has protective power when passed on.

Dacordobarro was raised by a foster “solo” mother, who brought her the first references from the feminine universe and the universe of work, affections and artistic expressions. Her mother was also a craftswoman, although she didn’t see herself that way. At home, she crafted many objects that her family could not afford to buy, “making the act of crafting things with her own hands very natural”.

As she grew, she gained new references from the layers of her own experiences. Her first time at a cultural center was at the age of 14, where she was able to see a visual arts exhibition. That was when she realized that forms of expression could also be seen as work..

One of the artists portrayed in the exhibition was on site and, according to Dacordobarro, he “blew her mind” as he explained that, although studying is important, becoming an artist takes much more than that: art is deeply connected to experiences and living.

This conversation defined her path. Dacordobarro, who had been keen on photography since she was 10 years old, found art a way of escaping the social roles that were assigned to her. She began incessant research work, deepening and expanding her expression by means of techniques like painting, “lambe-lambe”, graffiti, collage and digitized images.

This collage was displayed in several exhibitions and portrays the same street as that of work “Maior que as muralhas que criaram ao meu redor”. Paved over a river, it floods when it rains. The artist is portrayed in sitting position while using a bowl to bathe, an old habit that she is very fond of and takes her back to the times in which she had no running water at home. She explains that this work reflects her perception that nature is our mother and river water is breast milk.

Her determination took her to the School of Visual Arts at the University of Amazonas, making her the first literate person in her family and the first to attend university and experience work different from that where “people are not seen as human beings”. She is also the first in her family to be able to “speak in the first person” and travel through other spaces, in a process of “generational healing” in many respects.

Higher education provided her with a set of techniques and skills, but her pre-teenage experience with photography and collage has a deep connection to her work to this day. These are the techniques that allow her to overlap the memory, self-esteem and perception that she has of the city.

Dacordobarro notes that it took her a long time to see herself as a citizen within the urban space, a place that also builds culture, technology, science and knowledge.

In this sense, the many trips she embarked on across the country from 2015 onwards was fundamental. In 2018, “tired of the racism and lack of dialogue” that emerged around her on account of the new political context, she left the Brazilian North and began a two-year trip through the states of Maranhão, Ceará, Bahia, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Minas Gerais.

In this collage, the artist’s face partially appears, displaying a haircut that is “typical from the hood, more often used by men”. This work portrays overlapped events, images, smells, memories and thoughts throughout a seemingly ordinary afternoon in Manaus, when she went out to get a haircut, buy peach palm and have a tacacá.

On the top left corner, one of the cutouts portrays her hand holding her first cell phone, an object that “allows people to talk to each other and create bonds”. She says that her mother kept it, just as she hoards all objects from her childhood, ensuring access to memories that would otherwise be absent from her life.

The background, right-hand corner, reveals the image of a lamp post, a fragment of another work which Dacordobarro is very fond of, urban intervention “Crianças são sementes” (Children are seeds), performed in Niterói. Full of illegal electricity connections, the lamp post that is so characteristic of Brazilian urban outskirts is seen by the artist as the materialization of the idea of connection and coexistence between people, a familiar and welcoming environment.

Her adventure ended in 2020 caused by the Covid-19 pandemic. Upon returning to Manaus, for the first time she was able to recognize herself as one who belongs to the city. And she realized how precious and affectionate her memories of a place that was once that of violence and scarcity are.

Based on this new perception, Dacordobarro went on to develop series “Manaus 40 graus”(Manaus 40 degrees) and others in which she investigates the relationship between her body as a black woman that is involved in witchcraft, and the complexity of living in the black and indigenous diaspora in the Manaus city center.

The circulation of these works has allowed her to meet other people, reflect, speak, overcome prejudice, and above all, recover or build the self-esteem of having been born in Manaus.

This extraordinary artist has three different names, which are chosen according to the energy that is established when she creates work:

Kerolayne Kemblin is her legal name.

Skarlati is the name that her foster mother chose for her, but never made it official. She only learned of this name in 2020, when she found an old letter from her brother, who lived in Fortaleza, asking about Skarlati.

Dacordobarro is the nickname she received at the age of two, when her family lived on a palafita stilt house. Kerolayne had an accident and fell into a clay pit beneath the house. It was her mother who revived her. The nickname stuck, especially because the neighborhood that they lived in was so full of mud that the children’s feet were always dirty. It’s a loving way to remember that she was reborn in this place.